The history of West Indian immigration can be traced back to the 17th century when enslaved Africans from Barbados, Jamaica, and Antigua were brought to the British North American colonies to work on plantations. The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) sparked another wave of immigration with thousands of former enslaved people and escape enslaved refugees relocating to New Orleans, Charleston, Savannah, Norfolk, Baltimore and New York.

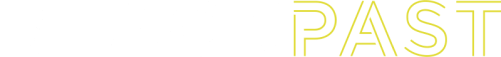

West Indian Immigrants in Boston (Globalboston.bc.edu)

After the American Civil War West Indian emigration to the U.S. grew significantly. The first wave of large-scale migration occurred between 1881 and 1915, when more than 250,000 most male laborers migrated first to Central America to help build what would eventually become the US-sponsored Panama Canal. Upon completing their work, many of these workers came to the United States. By 1930, an estimated 100,000 Black migrants from the Caribbean (used here interchangeably with West Indian) were living in the United States, mostly in New York, South Florida, and Massachusetts. Prominent early 20th century West Indian immigrants include comedian Bert Williams (Bahamas) black nationalist and Pan Africanist leader Marcus Garvey (Jamaica); Harlem Renaissance Writer Claude McKay (Jamaica), Historian and Bibliophile Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (Puerto Rico) and Harlem mobster, Stephanie St. Clair (Martinique).

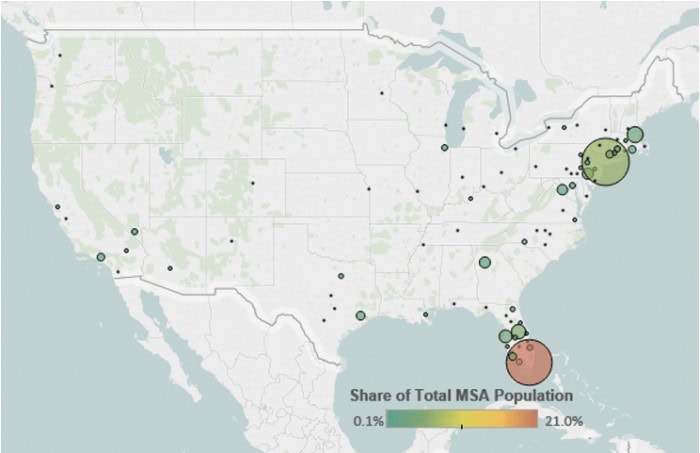

Map Showing Carribbean Immigrant centers in the U.S. 2019 (Migration Policy Institute)

While many people are familiar with the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to Northern cities after 1915, less well known is the parallel movement of people of African ancestry from the West Indies. This included people from the British colonies of Jamaica and the Bahamas, French colonies such as Martinique, independent nations such as French-speaking Haiti and Spanish-Speaking Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Puerto Ricans and U.S. Virgin Islanders already technically U.S. citizens, augmented these numbers. These emigrants, like the Southern migrants, sought jobs in Northern factories in the period between 1915 and 1940. That migration accelerated during World War II, driven by demands for defense plant workers, and continued into the post-World War II period. During the immediate post-World War II period, for example American companies across 1,500 localities in 36 states sought thousands of “W2” or contract workers from the Bahamas, Jamaica and Barbados. It is estimated that about 50,000 English-speaking West Indians alone settled in the country between 1941 and 1950.

Major immigration reform in the form of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 for the first in U.S. history allowed entrance into the nation based on needed skills rather than region of origin. As a consequence, immigration from the Caribbean grew dramatically. By 2001, an estimated 2.9 million West Indian immigrants resided in the United States. These immigrants and their descendants created vibrant communities in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Miami, and Los Angeles.

In 2005, California Congresswoman Barbara Lee introduced a bill to designate June as Caribbean Heritage Month to “celebrate the contributions of millions of Caribbean Americans to the United States since the inception of the country.” Notable West Indian first and second-generation immigrants include U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, award-winning actor and director, Sir Sidney Poitier, entertainer and humanitarian Harry Belafonte Jr, political activist Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure),. entertainer Wyclef Jean, professional athlete Carmelo Anthony, and former Utah Republican Congresswoman Mia Love. Today, the Caribbean remains the largest region of birth (45.6%) for Black immigrants who in 2020 made up 1.3% of the total US population.