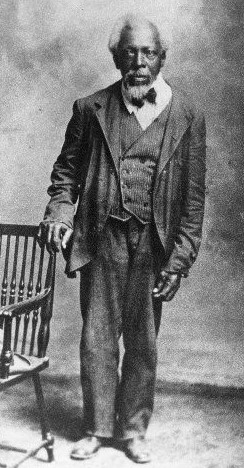

Born a slave under the name “Toney” in 1791, Anthony Weston eventually became the patriarch of Charleston, South Carolina’s elite free black family, the Westons. Weston began his life as a biracial enslaved person who worked as a millwright. Eventually, however, he supervised the construction of the mills that processed the crops of his owner, rice planter Plowden Weston.

A grateful Plowden Weston included in his will a provision for Anthony Weston to control half of his time (literally, after completion of daily tasks, time earned to pursue one’s own interests and ambitions) and to train his successors. The will also stipulated that Anthony Weston would be granted full control of his time in 1833. As indicated in the will, these provisions were based on “In consideration of the good conduct and faithful valuable service of my mulatto man Toney….”

Following Plowden Weston’s death in 1827, Anthony Weston was virtually free, although he could not be completely emancipated because of a provision in the South Carolina Slave Act of 1820 stipulating that the emancipation of an enslaved person would also have to be recognized by the state government. Furthermore, Plowden Weston’s will did not appoint an owner in trust for Anthony Weston, so he lived under the threat of being seized by the state and sold at auction.

Weston nonetheless worked as a “free black” in Charleston. His good reputation as a millwright made him highly successful. By the late 1830s Weston’s business had grown to the point that he himself acquired slave laborers. Legally unable to own property in the state of South Carolina, Weston’s slaves were ostensibly held by his wife, Maria, a free black woman. Maria Weston purchased twenty slaves between 1834 and 1845. At the time of the 1860 federal census, Anthony Weston’s assets were valued at $13,000, and Maria Weston’s holdings in real estate and in her fourteen slaves were taxed at their assessed value of $40,075. Weston’s wife purchased several of the slaves at their own behest, thus allowing them to live similar lives of virtual freedom. Weston assisted some of the slaves in purchasing their own freedom. Most of the evidence, however, points to economics as being the main reason for the Weston family’s ownership of slaves.

Weston’s favorable standing and biracial ancestry afforded him a place in the Brown Fellowship Society, Charleston’s most elite free black organization. At the outbreak of the Civil War Weston and several other black Charlestonians sent a letter to Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens pledging their support for South Carolina’s independence claiming, that their blood, after all, was at least half white. Weston, however, was not entirely dismissive of his black heritage, as he called for missionary expeditions to Africa by black Charleston church members to enlighten “their fathers,” and to “inform the enlightened that we should like to come home.” This statement has been interpreted by some historians to mean he supported emigration of African Americans back to Africa.

By 1880, fifteen years after slavery ended, the real property of Weston’s estate was assessed at only $19,000. Like other slaveholders after the Civil War, the Westons felt the effect of the uncompensated emancipation that came with the passage of the 13th Amendment. The date of Anthony Watson’s death is unknown.