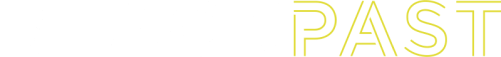

Julien Raimond was a wealthy indigo planter in Saint-Domingue. He is known for his political pamphlets and his struggle with the French National Assembly for racial reforms in the colonies. He helped write the Constitution of the newly-independent Haiti.

He was born in Bainet (southern Saint-Domingue, present-day Haiti) on October 16th, 1744. He was born to Pierre Raimond, a white French planter, and Marie Bégasse, a free mulatta, daughter of a planter. The wealth of his family allowed them to be considered part of the island’s elite despite their color, and for Julian Raimond to receive a high quality of education.

In 1784, Raimond left for France where he started his political activism to fight for the rights of the free colored people, writing manuscripts about colonial racism to the French Government. Initially, he was neither an abolitionist (he owned over 100 slaves), nor a proponent of Saint-Domingue’s independence. In 1789 he started taking up more abolitionist views upon joining the group Amis des Noirs(Friends of Black people) with Vincent Ogé. After some unsuccessful petitions for colonial voting rights to the French government, the group stopped meeting, and Raimond and Ogé politically parted ways.

In 1790, placing himself as the representative of Saint-Domingue’s free colored people, he wrote a powerful list of demands to the French government, in which he laments the inequality of colored people before the law, and the lack of their representation in the government. He made his requests on the basis that free people of color payed taxes, and therefore deserved equal rights.

In May 1791, just a few months after Ogé’s execution, Raimond convinced the French Assembly to give the right to vote to free colored people in colonies, which, because of the opposition of the island’s white minority, contributed to the slave uprising of August 1791.

In August 1790, Raimond had sold all of his slaves and began campaigning in favor of gradual abolition. In 1793, after he demanded the abolition of slavery in all French colonies, Raimond was arrested and charged with causing discord in Saint-Domingue; he was incarcerated for 14 months.

By 1800, Raimond’s views on Saint-Domingue’s independence also changed as he allied with independence leader Toussaint L’ Ouverture to write Haiti’s constitution. Raimond died shortly after the constitution’s promulgation in 1801, at the age of 57.

Although most of his political activity took place in Paris, Raimond’s activism on behalf of free people of color and later all Haitians, played a very important role in Haiti’s Revolution. As opposed to other colonial activists for racial change, Raimond never fought physically but instead with his political essays. He represented the more conservative elements of mixed-race Haiti that were finally persuaded to support the Revolution.