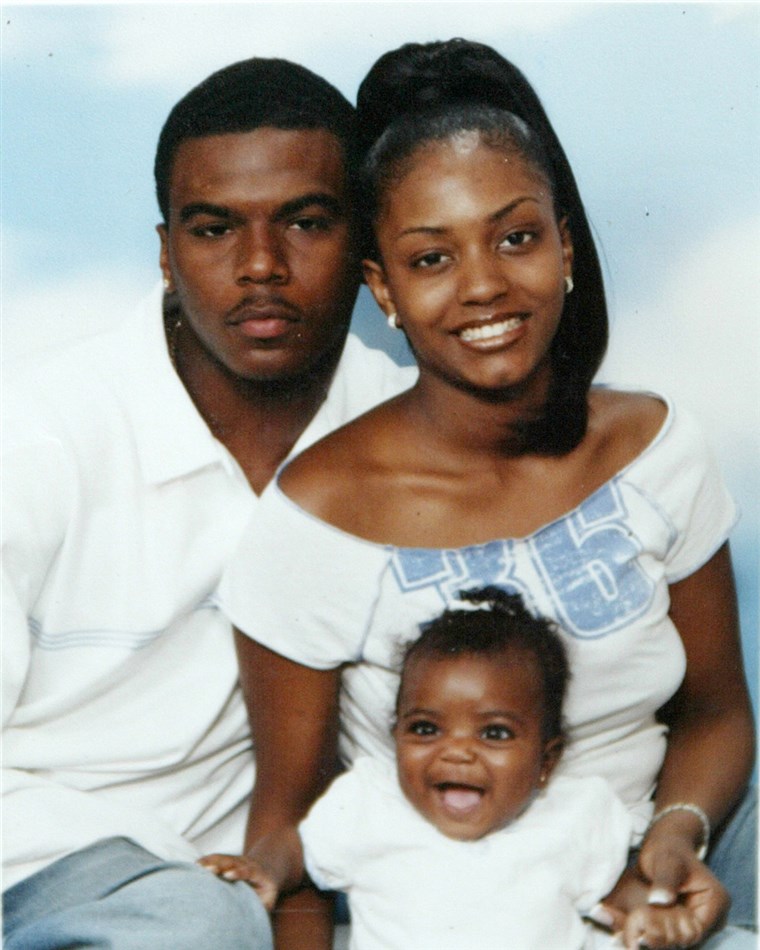

In the following article, Henry W. McGee, Jr., a Seattle University Professor of Law and Central District resident, discusses the recent dramatic transformation of the area from a predominately working class African American community into an area of high income white, Asian American and African American professionals. His article suggests implications for black communities across the United States.

In 2006 former Seattle mayor Norm Rice, the city’s only African American to hold that position, summarized his frustration over the paradox of gentrification at a community forum in Seattle’s Central District. “I’m concerned and I am frustrated because I don’t know what the alternatives [to gentrification] are. [This process] clearly isn’t racist, it’s economic. The real question you have to ask yourself is: Is this good or bad?”

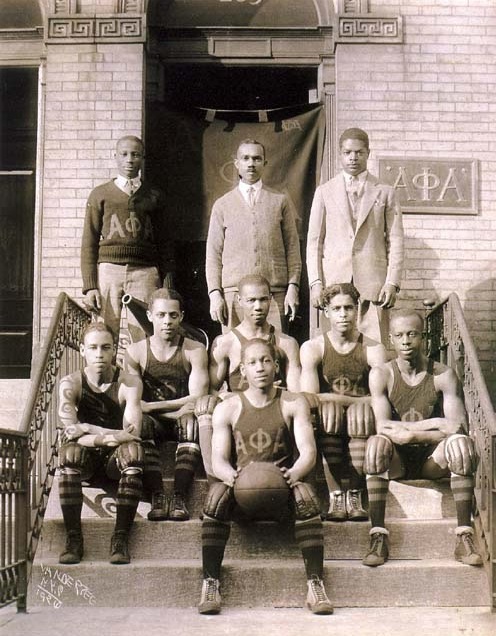

The transformation of Seattle’s Central District and its African American residents is not unlike the story of many American cities. New York City’s Harlem, Chicago’s South Side, South Central Los Angeles, and San Francisco’s Fillmore District, to name but a few, have all seen once-shunned black districts populated by the children of “white-flighters” who now crave the proximity, convenience, and “hipness” of living close to downtowns where they work and play. This process commenced ironically as the 1960s Civil Rights Movement wound down but is increasingly a reality of 21st century urban America. Traditionally one of the most concentrated of all of the nation’s inner city groups, many African Americans are moving out of the urban core and into the suburbs.

But unlike the cities in which African Americans reside in significant numbers, Seattle, and Washington State, have relatively small black populations. Moreover, African Americans are not the largest population of color in Washington State. The 2000 U.S. Census reported that 190,267 African Americans resided in the state whose total population was 5,894,121. Seattle had 55,611 African Americans. The census also reported the statewide Latino population as 412,509 with 29,719 living in Seattle. The Asian American population was 395,714 and 84,649 respectively.

In King and Pierce Counties, Washington’s most populous counties which also have the vast majority of the states’ African Americans, the percentage of whites dropped considerably between 1990 and 2000. Seattle, Federal Way, Renton, and Kent, the four King County communities with the largest black populations, remained predominantly white. The three suburbs saw huge black population increases over the 1990-2000 decade, and continue to experience heavy growth. The percentage of blacks in Seattle dropped in the same period.

There was also a dramatic shift in the racial landscape of the Central District, Seattle’s traditionally African American community. In 1990, there were nearly three times as many black as white residents in the area, but by 2000, the number of white residents surpassed the number of blacks for the first time in 30 years. The overall racial shift in the Central District is clearly in favor of white in-movers, with a concomitant number of blacks moving out.

Looking beyond the gross numbers the Census reported subtle but significant changes within the Central District community. The overall percentage of households reporting incomes of $50,000 or more has risen substantially. Most black families in the area report incomes of less than $15,000 and these low income families comprised a smaller percentage of the total households in 2000 than in 1990. In 2000 most of the area’s residents between 22 and 39 were white or Asian. Most blacks, in comparison, were either under 22 or over 60. These percentages suggest that there are fewer blacks in the District in prime income earning years. The white and Asian American residents of the community are also generally better educated. Their presence, and the presence of their children in Central District schools, has increased the “education gap” between black and white children and adults. The Central District, for blacks at least, is increasingly becoming a community of the very young or the very old with many better educated, working class African Americans moving southeast into Seattle’s Rainier Valley or beyond into Renton and other inner suburbs.

Ironically the promulgation of anti-housing discrimination legislation has encouraged this movement. In 1977 Washington passed two anti-discrimination statutes, the “Mortgage Disclosure Act,” and the “Fairness in Lending Act.” These measures made the trickle of blacks into the suburbs in the 1960s a flood by the early 1980s. At the same time younger European Americans, concerned about rising gasoline prices and attracted by the urban lifestyle their parents had fled a generation earlier, began to seek out the Central District which in the 1980s was made even more attractive by depressed housing prices, a consequence of decades of redlining that was finally on the decline. Young European American childless couples, or those with young children, now purchased properties in Central District neighborhoods their parents, with few exceptions, would have regarded as racially contaminated.

Anecdotally, I have lived literally on the northeast boundary line of the Central District since 1994. I can affirm that the passengers on the bus I’ve taken to work each day over the past decade have become whiter and whiter as it traveled through the community. Indeed during rush hour when office workers and professionals take the 20 minute bus ride downtown or back to their homes, I am often the only African American on board.

Although working class and moderately affluent African Americans have abandoned the Central District for housing bargains elsewhere, there is little doubt that continued racial discrimination has also played a role in their displacement. In a 2003 study of discrimination in home mortgage lending, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) discovered that Seattle African American loan applicants were 2.56 times more likely to be denied a conventional mortgage loan than white applicants in 2002. And a national study by the Center for Responsible Lending indicated in a 2005 study of data released by lenders themselves showed that people of color were more likely to pay high rates for mortgage loans. Such loans require borrowers to pay tens of thousands of dollars in additional interest while building less equity. Borrowers who fail to repay these loans lose their homes, ruin their credit, and damage neighborhood stability. Viewed for decades as a prime example of institutional racism, redlining has unquestionably declined. It has also morphed into more subtle and arguably even more insidious forms. .

Moreover gentrification which has increased home values has also increased property taxes. Many African Americans who had paid off or paid down their mortgages after twenty or thirty years in their homes saw spectacular increases in the value of their properties, particularly in the 1990s and the first years of the 21st Century. One three bedroom, one bath, 1,200 square foot Central District home assessed by King County as valued at $1,280 in 1938 was worth $5,000 in 1960, $190,000 in 2001, and $355,000 in 2005. Those on fixed incomes or those with modest incomes often found themselves with tax bills larger than their annual mortgage payments. Yet their low incomes prevent them from acquiring loans to repair or upgrade their properties, forcing them to sell to younger, more affluent, and credit eligible buyers who in many instances were white. Not surprisingly the percentage of black Central District homeowners has been steadily declining for the past three decades.

The Central District, which took seven decades to achieve its racial identity as a predominately black area, has in the last two decades become much more racially diverse as European Americans have discovered its attributes. Yet this is not simply a story of whites replacing blacks in a community. First, many black residents who can, stubbornly remain. There is also a growing population of other people of color, including substantial numbers of recent arrivals from Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

The ultimate question then is not the fact of change, but the nature of it. Will the Central District become an urban rarity, a viable, vibrant interracial community, or will it do a reverse “flip” and become an essentially nearly all-European American area? The “flip” argument is predicated on the pattern of racially segregated neighborhoods which remain the national norm.

Yet, there are indications that racial attitudes are in flux and that racism itself is no longer the primary bar to residential integration. A recent study in the American Sociological Review noted that:

“A powerful interracial tide has transformed friendships, dates, cohabitations, marriages and adoptions in just one generation. If the wave continues to grow, it could sweep away racial stereotypes and categorizations, as well as the rationale behind affirmative action and other broad minority protections. For now, the interracial trend – while evident everywhere – is hard to gauge because young adults and children are at its vanguard . . . . [T]he wave is so far-reaching that the average American today, young or old, is 70 percent more likely than Americans were a generation ago to count a person of another race among his or her two or three best friends.”

This development suggests that the chances for a permanently viable interracial community will turn more on economics than on pressure from any racial group. Social class, more than race, may determine the urban demography of Seattle and other cities throughout the nation. As one writer recently observed:

“[P]laces like New York and San Francisco appear to be richer and more dazzling than ever…. But middle class city dwellers are being squeezed out by the rich as much, or more so, as by the poor, [they are] a casualty of high housing costs and the thinning out of the country’s once broad economic middle. The percentage of middle-income neighborhoods in metropolitan areas like Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington has dropped since 1970. In New York, the supply of apartments considered affordable to households with incomes like those earned by starting fire-fighters or police officers plunged by a whopping 205,000 in just three years, between 2002 and 2003.”

The loss of middle-income city residents has more impact on the poor who remain behind, making it harder for them to become homeowners, send their children to better schools, and make the kind of personal contacts that can be a route to better jobs.

Seattle is a prime example of this trend of middle class decline. Recently it was reported that Seattle had but one “affordable [middle class] neighborhood left,” the remote Georgetown- South Park area. Very few middle class European Americans or African Americans will be able to survive the upward soar of Central District housing prices. Instead, the community will be increasingly populated by high income “techies” and professionals of every race.

This ever-increasing concentration of wealth could mean Seattle will become the gilded city of the upper-middle and upper classes. Seattle has recently been called a “superstar city” by urban demographers. It’s not quite in the same league as San Francisco and New York, but census data shows that Seattle housing prices have grown faster than the national average for the past half century from 1950 to 2000. In these superstar markets, including Seattle, the price of housing is driven by the incomes of its wealthiest citizens, not middle class residents. This means that house prices can grow faster than the incomes of existing residents if there are enough new affluent residents from outside the metro area who can afford purchase homes.

Seattle has become the domain of high-earners. Between 1990 and 2004, households earning more than 150 percent of median income ($90,000 in 2005) expanded faster than any other income category and now comprise 250,000 households, one-third of Seattle’s total. In King County, first time buyers in 1995 had 65.6 % of the income needed to purchase a low-priced home. By 2005 only 44.7% were in that category. Moderate and low income renters face a similar challenge. In 2005, some 2,000 Seattle rentals units were lost to condominium conversion. Another 681 units were lost to demolition.

Most observers in Seattle and across urban America have been concerned about the racial displacement that seems to inevitably follow gentrification. Those concerns miss the mark. The gentrification of the Central District, and much of Seattle, is much more about class than race. What is clear is that thousands of African Americans have been displaced from the city’s oldest identifiably African American community. Who will ultimately replace them is at the moment far less clear.

_________________________________________________________

The full version of the article may be found at: “Seattle 1990–2006: Integration or Displacement,” 39 The Urban Lawyer (ABA) 167 (2007).